Robert Cubitt

…is our reviewer for the October-November 2015 Challenge, the last challenge of the year.

Bob retired from the Royal Air Force after 23 years of service, travelling the world and visiting places like Oman (a small island by the name of Masirah), Cyprus, Malta, Holland, Germany and various parts of the UK. After he retired from the RAF, Bob worked for the Royal Mail as part of their logistics team and stayed with them until 2009.

With time to spare Bob returned to writing with a passion and produced two works of fiction in rapid succession. These had been “works in progress” while he had still been in full time employment and just needed finishing off. Since publishing these books on Amazon he has focused on new projects and now has a total of four fiction and three non-fiction works published, with more in the pipeline.

You may read about Robert Cubitt’s books here:

We had two entries for the challenge and while one is being worked on for publication, the other one is here for your reading pleasure. Well done both Nilanjana Bose and Gerard Bracken! And thank you for participating.

THE CHALLENGE

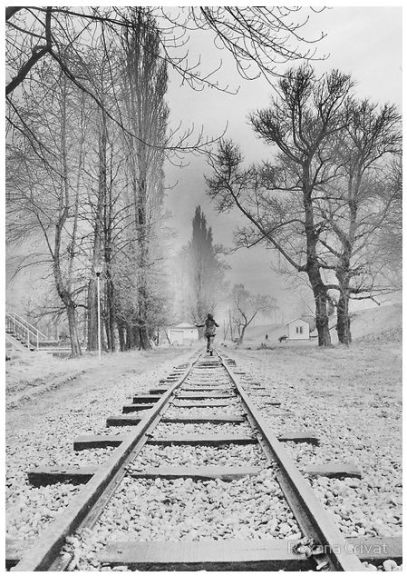

For the first time we had a visual challenge. Our entrants had to develop a story in 2000 words or less, based on this picture

Thrown Off-track

by Nilanjana Bose

From Payradanga the tracks run a gentle South-West towards Naihati and then onto Sealdah, straightening at some point almost due South. If Shankar boarded early enough he got a window seat. He climbed into the car now, swinging himself with practised ease over the gap between the platform and the footboard, and went straight to the back end. The seat was empty and he settled down, his sense of mini-triumph failing to spark today.

The train snaked through paddies already alive with the field workers at their sowing. A woman at a communal manmade lake slapped a twisted saree on a flat stone to get the dirt out, a dozen sarees washed already, flapped on a line like giant flags. The line was tied to four slim long branches held together in two unequal Xs, itself holding them together and being held in place by them in turn. Much of his life felt like that unequal X sometimes, tied together with the presence of various strings, each anchoring the other, all at the mercy of the winds. Anything could come undone anytime.

The tracks connect more than the suburbs to the throbbing heart of the metropolis, they crisscross between paddies and orchards and factories and brick kilns, cutting up the land into neat little portions, urban, suburban, semirural, rural, backward. They cut through and classify things in myriad insidious ways, tie and unravel many unequal Xs many times over.

The train drew into Naihati junction, there was much hubbub as passengers got on and off. A gaggle of vendors boarded, there was some on-going altercation at the entrance between one of them and a commuter, but before it could be satisfactorily resolved, the EMU local blared its horn and pulled out in long drawn, smooth bursts of acceleration, like a telescope unfolding. Shankar leaned back and closed his eyes, aloof from it all. The events of yesterday still clouded his morning.

***

When the tracks were laid more than a century ago, the banyan sapling must have been a good distance away from the sleepers. But now it had unfurled a monumental canopy overhead, its aerial roots touched the ground, formed woody twined trunks and the whole grove almost bordered the raised embankment. Shankar’s hideaway inside it had been devised in teenage, he and a few close friends had claimed it. A few miles from the station, well out of sight and earshot of home. In time they finished school and Manu, Ratan, and Tipu had moved away to the city and beyond. No-one came to the banyan except Shankar now.

He was the only one who stayed back, doggedly commuting every day to a job in the city. There was an ailing grandmother, a younger sister, a widowed mother knitting up cardigans for her small clientele on a second-hand knitting-machine. Moving out was not an option. He still came to the old haunt for some lazy trainspotting in the weekends sometimes; on an early evening after work for some downtime. Over the years he had got to know this home stretch of the track well, the silence and the heat haze on them in a summer afternoon, the sound of them when they hummed with the approach of a train. He could pinpoint the times the locals passed without having to look at his watch.

The other three visited on the major holidays in autumn, they met in the public marquees for the Goddesses – Durga, and Lakshmi and later Kali; the evenings raucous with the new music releases on the loudspeakers, lit with fairy lights. Their lives in the cities seemed characterised by an acute shortage of time, all was change at a fast clip – people moved, jobs changed, buildings came up, every year they had a new set of neighbours. By contrast, the only people that had moved into Payradanga in all this time was the new postmaster, the older one had retired just a month ago.

When Shankar pointed this out to the group on the day of Kalipuja, it turned out that Ratan – who no longer called the festival by its local name, instead said Diwali like any northerner now – knew the family. But apart from them there were no new faces, most families had been around for years, settled into their respective grooves, only the young people steadily crumbled away from the homesteads in search of livelihoods.

***

Shankar spotted the girl on a day off, just weeks before Holi. He had come to the banyan with a rug, a few snacks, and a new book. He looked up between two pages, and she was running between the tracks, her movement fluid, her toes touching down unerringly on the wooden sleepers each time without breaking stride, quite unaware of her surroundings. The train was due, he knew that vaguely from where the sun was in the sky, in fact he could hear a train at the platform, a long honk a few miles away, sounds carried far in still mornings over the fields. He sat motionless, paralysed with unease and indecision for a split second, and then he was out of the grove and running towards her with all the speed he could muster, shouting at the top of his lungs.

“Move out, move out, train’s coming.”

She did not stop and kept running, the same measured pace, touching down light footed. Shankar could hear the lines humming now, the girl was still out ahead of him, unaware or maybe uncaring. He stopped shouting, channelled every bit of energy into drawing alongside her, the gap between them narrowed now, but so also the distance between them and the roaring monster behind. His heart felt as if it would explode inside him if he had to take one more stride, the train honked angrily again, too close now for comfort, the noise too loud in his ears, the sound of the wheels harsh, the rushing column of wind that signalled its arrival, all felt like inches away. With one last extraordinary effort he leaped and drew abreast, unceremoniously yanked her off the tracks. They both tumbled onto the embankment in a heap of flailing limbs and kept rolling over endlessly while the Ranaghat Up passed with a deafening burst of noise above them.

Shankar found his feet unsteadily, shaking with the reaction, “Are you crazy, girl?”

He had seen her around the place, strangers stuck out for miles here, though their paths were unlikely to cross. She was the daughter of the new postmaster. He noticed that her jamun-dark eyes were fixed somewhere near his chin. Involuntarily he rubbed his nose, ran a hand over his jaw, “Can’t you hear or what?”

For an answer, she dealt him a resounding slap and walked off across the fields. Shankar was too non-plussed to protest. He stood gaping, rooted to the spot. When he came back, the book refused to settle him, his nerves jangled and would not be soothed. He rolled up the rug and with a sense of great anti-climax started off home. The whole day had somehow been completely ruined.

***

Shankar strolled into the banyan grove after work, the moon was a few slivers away from being full, enough light to see clearly by. There was a white patch on the ground beneath a pile of darker things. It was a face-towel, topped by a scrap of paper, weighed down by a pack of coconut laddus carefully sat into a terracotta dish, nested into another of water to keep ants away. Shankar opened the pack, sniffed – they were quite fresh, the ghee had soaked into the paper liner in a large smear; he ate one and looked at the note by the light of a match.

“Sorry! And thank you – Joba” was scrawled on it in great looping letters, generous and forceful. Shankar smiled and struck a match again. He wrote a reply on the other side, and arranged it back again exactly the same, weighted with the dish of water. He waited as long as he could, but no-one turned up. The cigarette burnt to a stub, there was no further pretext to linger. He left, taking the laddus with him.

He got through his evening distractedly poking around. Maybe she was not expecting a reply, maybe he was reading too much into a simple gesture, it was perhaps only an apology not an overture. Maybe some animal would move the dish, spill the water and smudge the words, why had he not thought of emptying it out? Maybe the winds would blow away the scrap before she came back, had he chosen the words right? It would be Holi in a few days, maybe he would see her out with the colours, take a chance on splashing some on her too. Ratan should be home for the festival surely, Shankar would cadge an introduction somehow.

But Ratan did not come. Shankar heard that work would keep him away till the end of spring. He could not quite bring himself to ask about Joba over the phone, it just felt too weird. As with the note, he did not have words the right size. Meanwhile, he checked on the banyan every day. The dish soon dried, then overturned and cracked, and the scrap of paper blotched with dirt before it was blown away. Shankar never knew if his rejoinder found the recipient.

The post office remained closed on the day of Holi; Shankar saw no-one from the postmasters’ family. He went out with Tipu and Manu like he did every year. The whole street was a mass of colours, the abeer and rainbow jets of water staining the tarmac and whitewash and white clothes in merry splashes, the powder thrown up in clouds colouring the very air they breathed. Shankar kept an eye out, but did not chance upon her anywhere.

Manu and Tipu left in a couple of days, and Shankar could not find the right conversational slot to mention Joba to them. And what was there to talk about anyway? A sudden accident averted, a slap for his pains, a pack of sweets and a cryptic apology – how could one explain them and their sudden impact on him without sounding cheesy? It niggled at Shankar – why had she run like that towards certain death? why the slap and the note? and why should the whole thing shift his priorities one infinitesimal bit even?

He saw her a few days later, across the carriage in the train returning from Sealdah. She stood alone near the door, a stray lock of hair fluttering across her face. He smiled tentatively, she returned his greeting. He walked alongside her as they left the platform.

“Can we walk to the banyan?”

Her eyes were still fixed at chin level, she would not lift them up to make eye contact with him. Her answer was indistinct, delivered in a flat monotone, “I take a rickshaw home.”

The rickshaw stand was not more than a minute’s walk, so he would have to make it quick. He said everything in one long rushed breath, keeping his face lowered, his gaze fixed on the paving. They reached in no time, she interrupted him with a non-committal smile, got into a rickshaw which pulled away smoothly.

Shankar finally brought it up with Ratan, worked Joba’s name into the conversation one morning over phone, clumsy and circuitous. Immediately Ratan’s voice cackled in his ears, “Why, dude? Are you thinking of sending a proposal or what?”

“Oh, come on, Rottu! Can’t a guy –”

Ratan broke in without paying the least attention, “Well, she is a lovely girl, unattached from what little I know. Pretty brilliant at sports and all that. You’ll have to learn sign language though. She’s deaf, lost her hearing when she was a child. Meningitis or something. But she lip-reads so well you’d never make out.”

~~~~

Glossary

Payradanga, Naihati, Ranaghat – towns/villages in the Greater Kolkata area

Sealdah – a railway station in Central Kolkata

Laddus – a type of Indian sweet

Abeer – powdered colour used for Holi

Holi – a spring festival where colours, dry and liquid, are splashed on friends and neighbours

Durga, Kali – goddesses signifying Shakti, the female form of Divine energy. The worship of Durga during autumn is the major festival in Kolkata and its surroundings

The Iron Road

by Gerard Bracken

Annie could feel the tightness grasp her lungs as she willed her legs to keep moving at a pace to match the railway ballast gaps between the shining frosted rail sleepers while she compensated for the unevenness of the stone surface. All around her was shrouded in the drapes of the early morning icy mist.

The lone rail marker post ahead indicated one mile and uphill gradient to Mary field railway station, she ran past familiar landmarks, all was quiet along the rail track this cold winter morning with most of the town’s people congregated at the station.

Barry was in single line with all the young army recruits, there was an air of youthful eagerness and enthusiasm about the adventure that lay before them. As the column halted in front of the station house, he could see his father and mother in the crowd among a sea of red waving flags and hands.

He picked out his father’s face, a mix of pride and dread, pride that his sons volunteered and dread at what lay ahead in the old country, Europe. He wished he was young enough to be there to share their fears, to climb up that trench ladder into the fiery abyss, to console them when they lost their comrades and lay with them in their last moments should it come to pass.

His mother eyes were red and glazed with tears, for years she had seen off her husband and sons to the mine at the start of each shift and feared that its dark dank interior would steal them away forever, entomb them in a sarcophagus of coal, now the talons of war had reached their small town and would sweep up its men into a maelstrom of death and destruction. She had brought them into the world in the sharp physical pain and soothing love of birth, she did not want to bear the pain of their loss.

For all of Annie’s best efforts to run along the ladder like track, the rail marker posts were not coming up fast enough and she calculated she would not make it to the station in time. She was coming up on the footpath to Breeches junction, she decided to take a short cut and make for the old disused timber water tower by the over grown mine rail siding.

The Iron Road with its four-foot-eight-and-a half-inch Stephenson standard gauge track followed the meandering river path along the valley floor; the twin tracks meant many things to many people over the years. Everyone who was born, lived and died in the town was connected to those two long steel lines that ran through generation after generation as it did along each bend and curve of its snake like path. Annie and Barry were two young people whose lives were divided by and joined by the track.

The main employer in the town of Tocher was the coal mine, which ran deep into the sides of the valley with tilting seams of coal excavated by men and for a time young boys on their backs in 10-hour shifts. This was the town’s main source of employment and income. In the great tradition of coal mining towns, the Iron Road divided the town physically, economically and socially.

On one side of the divide was a mining family called the Dixons, originally from a North England coal town, they could proudly trace back their descendants 5 generations to coal miners. They lived in the shadow of the mine on the Broadlands estate which was originally built by the mining company.

Barry Dixon was the next in line to join the mine, his father and two brothers all worked there, they were miners through and through: brave, hardworking and hard living men. Barry was different, he was quiet, gentle and an avid book worm who spent all his spare hours at the back wall looking at the trains and waving to drivers and passengers alike. He was in the top five at the local school. Railways and trains was his passion and he wanted to be a rail Engineer. His father, Big John, had shovel sized hands and was built like a bear, he wanted Barry to follow in his footsteps and be a miner, his mother, Julia knew better, this son was destined for a different path to his father and brothers.

On the other side of the Iron Road and 2 miles away, in the better area of Saint Chalfont, was a spacious three story, detached Victorian house with lush ornate gardens also backed on to the track. Here lived the Clarendon’s who were of middle class stock from Scotland, whose lineage was that of doctors and solicitors. Arnold Clarendon, head of the family ran a busy medical practise in Bury Street for select patients, he had great plans for his two daughters. Annie Clarendon was the oldest, a keen academic, athletic and was destined to study medicine and eventually take over family practise. She was set for her departure at the end of summer to medical school.

Barry started to hang out at the railway station and stock yards in his early teens and after time got to know the rail hands. The yard chief turned a blind eye to company rules and regulations and encouraged him to ride on the foot plate and assist the drivers. Barry’s enthusiasm would spill over at family meal times and slowly his father could see that this son was not destined for the mines.

Barry’s family couldn’t fund a university education for Barry, the fees and lodgings were not within their reach. The yard chief had gone to the same school as Barry’s father and they frequented the same public house at the weekends. The topic of Barry’s love of trains came up in conversation and the yard chief mentioned the annual rail company scholarship.

Big John was a family man and wanted his sons close by in the mines but mining was hard, physical and dangerous work which, over the years, was etched into their bodies, he knew his wife constantly worried about them and he could see the relief in her face on their return after each shift. The ominous clouds of closure hung periodically over the mine and so, after much soul searching and discussion with Julia, they encouraged Barry to sit the scholarship exam and interview.

Barry scored high in the exam and won over the interview board with his working knowledge of the rail yard and was awarded the scholarship, he would leave for university in September.

Annie Clarendon’s family were of the Humanist tradition and were conscience of their privileged status in life. It was therefore important that they return this good fortune to the less fortunate.

The hospital set up by the mine company was in poor condition, under resourced and under staffed. Every Saturday, Annie’s father held a free clinic at the hospital for anyone who needed medical attention, at an early age; Annie would assist her father at these clinics each summer.

Barry got some paid work at the rail yard, while assisting the yard men shunting coal trucks, Barry’s hand got caught in the track switch handle, resulting in a cut and badly bruised hand, the yard chief sent Barry to the hospital.

When Barry’s name was called, he was seen by Arnold Clarendon, who after much pocking and prodding, deduced that no bones had been broken and once cleaned, the hand needed to be bandaged. The cleaning and bandaging was gently and expertly carried out by Annie, Barry sat there his heartbeat pounding in his ears as his mind waded through a river of words trying to string a meaning introduction sentence. In the end, he was afraid to say anything in case he sounded stupid. Annie, on the other hand blended medical speak, with comforting words and small talk as she went about her task.

After an awkward thanks and good-bye he headed home. They met each other at the clinic for the next four Saturdays to check the healing of his hand and apply fresh bandages. Barry savoured every moment in her company. Annie broke the silence, by picking a book she had read and recited its plot to Barry. Barry then followed suit. They agreed to read a different book each week and compare their understanding of its story line and characters. After the four weeks, knowing it was now or never, he bucked up the courage to ask her to meet him for walks along the tracks.

It was 1914, the Victorian era of separation of the sexes and class still lingered and two young teenagers from different upbringings meeting alone for walks would not have been tolerated in a small town with so many prying eyes.

During their trackside walks, they built a bridge of trust and understanding with stories of childhood, family, friends, books and interests, although they were breaking with the strictly tiered class hierarchy, they were conscience of their respective families’ positions within the towns separated communities, and not wanting to cause any more hurt should they be caught, kept their meetings as close friends and nothing else.

Barry would talk lyrically about the history of the track, the names given to the track sections and the bends, the train engines, their operating pressures, their individual mechanical quirks and dislikes and how the drivers could coax the best out of engine and truck wagons.

Annie described her privileged upbringing with nannies, a maid, a butler, holidays and her distant mother, who mixed with the town’s circle of socialites. She explained some of the basic medical procedures her father would let her assist him with and the odd behaviour of the more eccentric patients at her father’s Bury Street clinic.

Their plans were cut short by the news of war in Europe, Britain’s entry into the war was followed by Canada’s automatic entry, and there was unanimity across the country, in every city, town and village and across the class spectrum. The Canadian Prime Minister called for a national supreme effort offering assistance to Britain. Canada’s army and navy was woefully under prepared for the task ahead, yet in weeks, 32,000 men had signed up for the Canadian Expeditionary force, among them Barry and his brothers. Annie also signed up to the Canadian Army Medical Corps nicknamed ‘Bluebirds’ after the blue uniforms and white veils.

Barry received his departure orders like all the other town volunteers to board a special charted train for Valcartier Camp near Quebec City. With heavy hearts, Barry and Annie met for what could be their last walk along the same tracks that should have taken them to university and not to the battlefields of Europe.

They talked about their futures after what the newspapers headlined this short and glorious war, they spoke of love, careers and marriage, they had a plan. It was fitting that they should carve out their future by the tracks. The tracks had always been a metaphor for hope and uncertain future for so many people over the years as they stretched into horizon.

Barry settled into a window seat, his suitcase stored overhead, his brothers sat opposite grinning at him, he thought he should feel sadness and fear, but he did not, he had his bothers to protect him and he to protect them and a reason to live.

In his heart he knew that Annie would be by the track, as the train pulled away to a fanfare of cheers and band music, he could see all the yard men waving as the engines blasted their whistles. As the train picked up speed heading to Breeches junction, he looked for the old water tower and saw Annie for a split second and smiled.

Wherever the Iron Road took him; he had the love of family and Annie.

3 comments

Comments feed for this article

December 7, 2015 at 12:40 pm

rohini99

Well done Nilanjana! Keep writing.

December 7, 2015 at 6:56 pm

Nilanjana Bose

Thanks Rohini! I will 🙂

December 19, 2015 at 9:04 pm

BCWG

Look forward to reading more of your work